George Vasey has gone from curating exhibitions in the front room of his home to curating the world’s most prestigious art prize in just ten years. Along the way he has worked independently and institutionally as a curator for a diverse array of public and commercial galleries, and has shared his experience with emerging practitioners as a visiting lecturer at various universities. In addition to his curating, Vasey’s writing also regularly features in publications such as Art Review, Art Monthly and Frieze.

Following the success of the Turner Prize at Ferens Art Gallery in Hull, Vasey has now returned to the North East to resume his Curatorial Fellowship at Newcastle University. He spoke to Niomi Fairweather over coffee as he reflected on the achievements of the Turner Prize, and explained how his programme at the university’s Ex-Libris Gallery is opening up a ‘curatorial conversation’ in their Fine Art department.

Niomi Fairweather: So how does it feel being back in Newcastle after the Turner Prize?

George Vasey: It’ s been a busy old time! It’s taken a bit of adjusting post Turner Prize, which was an amazing experience. I keep describing the whole process to people as being attached to a rocket and closing your eyes for six months.

NF: It sounds intense.

GV: Working on that scale was a very new experience for me. I’ve tended to work with emerging artists in smaller institutions. With the Turner Prize I was really interested to see how larger organisations work and see curating as part of a much bigger structure. There were moments when you’d be sat around a table with about fifteen people trying to remember everyone’s name. It’s also important to say that I co-curated the exhibition with Sacha Craddock, who I knew a bit through us both sitting on the New Contemporaries board.

NF: How was it working alongside with someone like Sacha?

GV: I think it worked really well. Sacha has a huge knowledge of the British art scene from the last thirty years and we would have these long and intense conversations about everything!

NF: She’s also a different generation to you…

GV: Yes, as a curator I’ve always found it vital to work across generations and understand the genealogy of where things comes from. To me, this sense of working across generations is really vital in the art world especially as it can tend to be quite ghettoised in terms of age.

NF: The age aspect felt like an important part of the Turner Prize too?

GV: Yeah with the lifting of the age restriction. Lubaina Himid and Hurvin Anderson, who are both over 50, wouldn’t have been nominated previously. That felt like a very important step forward and people responded very positively to it.

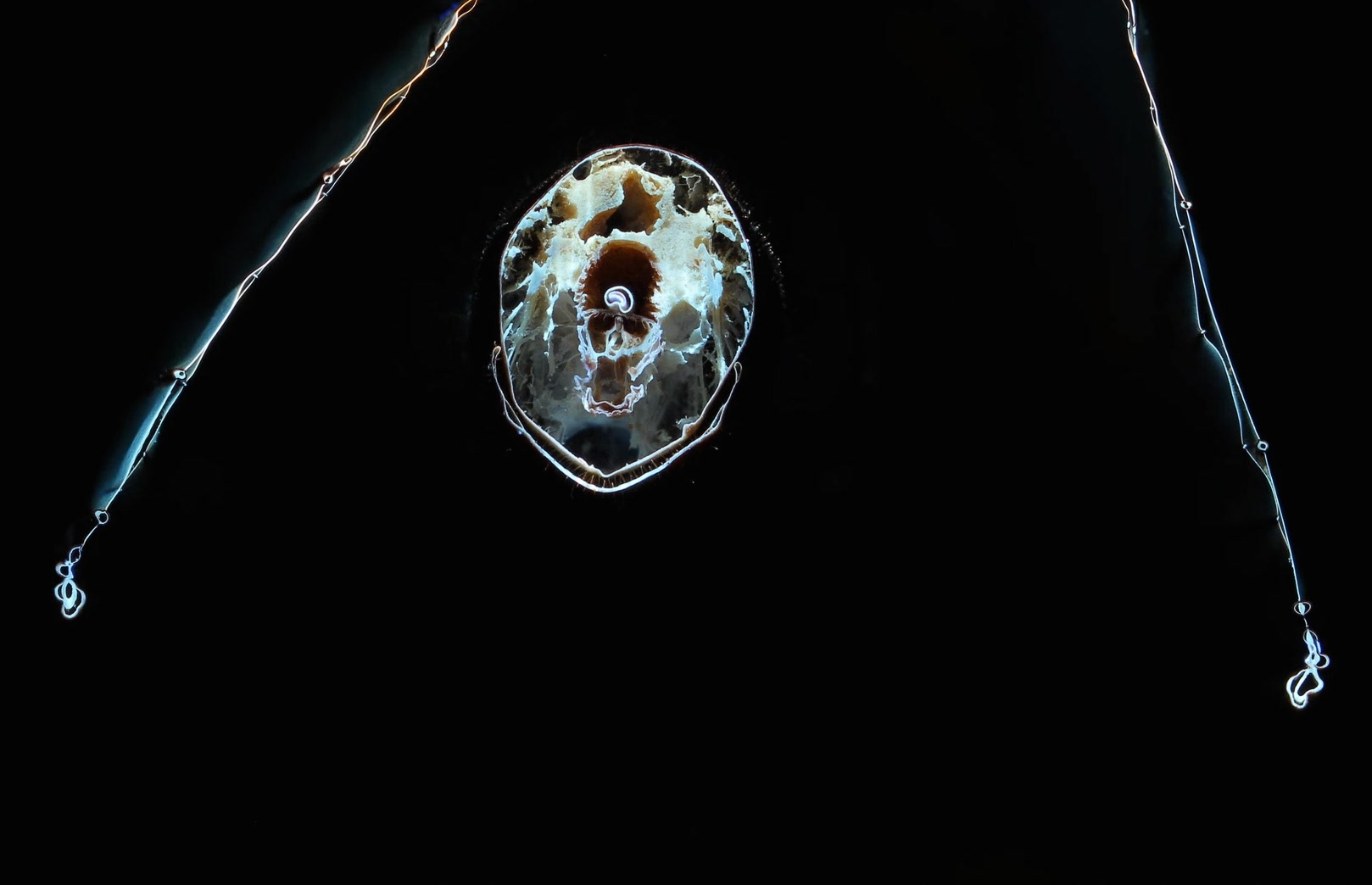

Le Rodeur: The Exchange (2016) by Lubaina Himid. The Turner Prize Exhibition, Ferens Art Gallery, Hull. Photograph by David Levene.

NF: You’ve now returned to your Curatorial Fellowship at Newcastle University; how have you found the experience so far?

GV: I graduated about four years ago from my MFA in Curating at Goldsmiths and since then it’s been non-stop. I think I’ve curated around thirty exhibitions! The fellowship has enabled me to take a side step and work in a slightly different way. I’ve really been trying to reflect and think about the kind of curator I actually want to be. What’s great is the fellowship is very nebulous: I haven’t really been given a job description other than to ‘bring a curatorial conversation to a fine art department’. I’ve been thinking a lot about repetition, care, porosity, slowness, and informality as curatorial methodologies.

NF: Are you enjoying the teaching aspect of the fellowship?

GF: I see very little difference between making exhibitions and teaching. My job is to be helpful to the students. One thing I find interesting is that a lot of students tend to police their thinking. Is pleasure okay? Is it okay to make beautiful images? These questions seem to raise a huge amount of anxiety in art schools. I think sometimes being a teacher is about permission and other times it can be a type of friendly antagonism.

NF: I think we’ve all been there. When you’re a student, particularly a fine art student, you’re always looking for acceptance, and maybe overall just that confirmation that your practice is interesting.

GV: I get it and I went through the same process. I thought for years I wasn’t intelligent or theoretical enough to curate; I thought I wasn’t reading the right books. I think a certain amount of validation just has to come from yourself. Recently I’ve started to think that the teacher’s role is to ask the stupid question — to get the stupid question out of the way so the students can ask the intelligent ones.

George Vasey leading a workshop at S1 Artspace as part of Syllabus II. Image courtesy of George Vasey.

NF: How are students responding to your programming of the Ex-Libris Gallery? Is the space creating a dialogue between you and the students?

GV: The programme has included events and workshops with Ruth Beale, Rosalie Schweiker and Anneke Kampman; and exhibitions with Felicity Allen and Anna Barham. All these artists’ practices offer useful models to the students. In February I established an open forum in the gallery that now meets every Thursday morning. We just sit in the gallery and chat, I’ve demoted myself to assistant curator and this informal forum take the curatorial lead. I’ve given the students a loose framework to work within, but they’ve really inhabited that space curating a series of exhibitions and events called Jane Doe. The university gallery should have porosity between production and display, between studio and public. Importantly it should be a place that enables productive failure.

NF: I think that dynamic is really interesting, and thinking back to my undergraduate degree I can’t say we had much input from a curator. I know you do a lot of freelance writing, are you offering advice in terms of text interpretation?

GV: I talk to the students about authority. What claims are we making for the work? Is it really the job of the curator to mediate? Interpretation is never static and neutral, different exhibitions demand different mediation. I think there is a set of fundamental questions here. What kind of public is the gallery for? Is confusion okay? Can artwork speak to everybody? Why should this art be made and displayed in this context right now? Interpretation will come out of those questions. Like I said, I just ask the dumb questions.

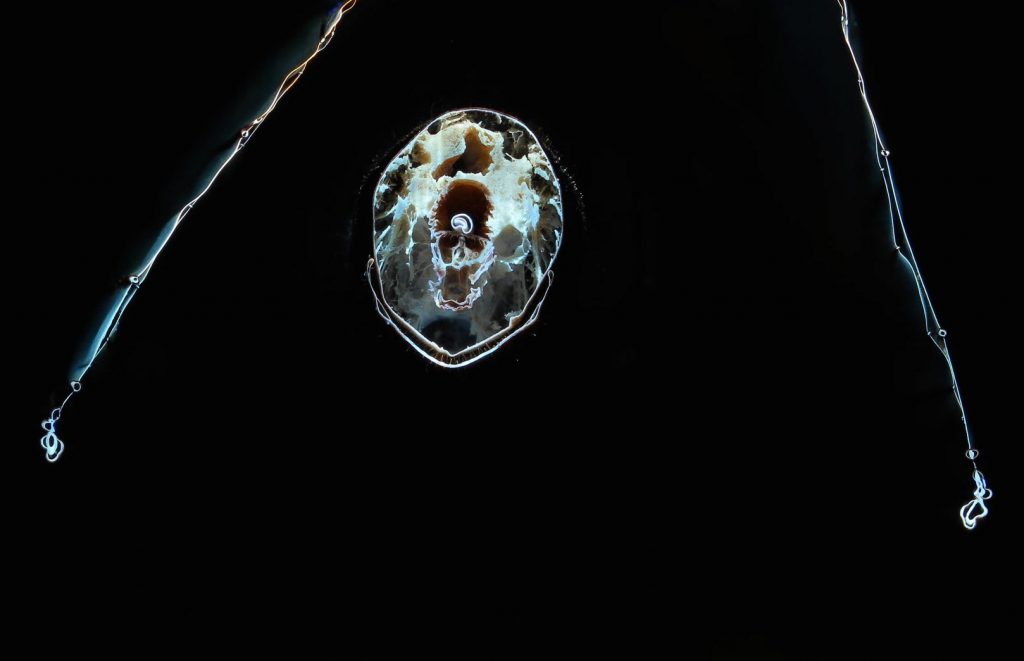

Sick Ardour (2018), Anna Barham. Image courtesy of the artist.

NF: Felicity Allen is the next artist you have at the Ex-Libris Gallery; I know she comes from a higher education background working in museum and gallery interpretation. Was the reason for wanting to work with her because of the position you’re currently in at the university?

GV: I met Felicity when I graduated; I was an intern at Tate Britain and she was Head of Learning. Over the last five years she’s gone back to a more studio bound practice. She’s created this neologism ‘The Disouevre’ which articulates the way in which artists who are peripheral to the art market have to adapt and work in many different guises. I think it is very interesting that as an artist you can make a painting and an institutional progamme. This is rarely talked about – how do artists work through and in institutions beyond the typical exhibition and project format? I thought that was an interesting conversation to have with the students.

NF: Do you think about how far you’ve come since your early curating days?

GV: I was thinking the other day that it’s been ten years since I started curating shows in my front room in London. I was still making work at the time, but I must admit, I don’t miss making work – not one bit! I have a deep admiration for artists, but I went in a different direction. I think curating is a hugely creative undertaking but most importantly it’s about helping artists with the things they need: time, money, space and dialogue.

Felicity Allen’s The Disoeuvre opens at Ex-Libris Gallery 18 April – 19 May.

George Vasey’s portfolio of writing can be found on his website.

Niomi Fitzsimmons Fairweather is an artist and writer based in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Published 09.04.2018 by Christopher Little in Interviews

1,454 words