Steve Pantazis talks to Dr. Marion Endt-Jones, curator of the exhibition Coral: Something Rich and Strange at the Manchester Museum.

Steve Pantazis: How was the concept of this exhibition born and what has attracted you to corals?

Marion Endt-Jones: I became interested in coral during my PhD research, which focused on the concept of the cabinet of curiosities in Surrealism and contemporary art (this fascination with coral is quite ironic really, as I grew up near the mountains and have never gone diving or snorkelling in my whole life). I was looking at how corals and other natural curiosities, such as trees, stones, fossils and insects, have been represented and displayed at different moments in history. Two post-doc fellowships allowed me to continue research in this area, and I approached Manchester Museum with an exhibition proposal initially in late 2010. I thought that, as a multi-disciplinary university museum, it was ideally suited to showcasing such a rich and complex topic from different angles. Nick Merriman and Henry McGhie were immediately enthusiastic and supportive, and the exhibition was scheduled for late 2013/early 2014.

Corals are endlessly fascinating and complex, and one of my observations was that a number of contemporary artists were interested in them as both a concrete material to work with (e.g. Hubert Duprat) and as organisms and symbols representative of wider concepts and themes such as metamorphosis, classification and ecology (e.g. Ellen Gallagher, Gemma Anderson, Mark Dion). Coral has been, and still is, difficult to grasp and classify – commentators have described it as ‘extraordinarily ambiguous’, the ‘site of an error’, and a ‘totalising monster’ – and such a ‘boundary object’ ideally lends itself to questioning social, political, cultural and scientific categories.

I’m also trying to convey the cultural (rather than economic or medicinal) value of coral; my research shows that an appreciation for coral has been deeply rooted in the collective cultural imaginary since antiquity, and it is absolutely heart-breaking to consider the rich tradition we currently put at risk by polluting, overfishing and acidifying the oceans.

SP: Was it difficult to work with people from disciplines different from your own, such as archaeology and science, in order to present such a wide vision of corals?

MEJ: The idea of interdisciplinarity very much lies at the core of both the exhibition and the accompanying book. It is an approach that, in my view, ideally reflects the complexity and richness of the topic – but it also has its shortfalls. For the exhibition, I was able to draw on Manchester Museum’s collections and the curators’ expertise, as well as commissioning artworks and bringing in loans, which has certainly contributed to the show’s appeal – one of the aspects visitors seem to enjoy most is the diversity of the material, the fact that it contains scientific specimens, but also artworks and cultural objects.

Each curator advised me on relevant objects from their collection to include; David Gelsthorpe who looks after the Earth Science collections, for instance, presented me with various coral fossils, of which we selected five for the final display. Campbell Price (Egypt and Sudan), Keith Sugden (Numismatics), Bryan Sitch (Archaeology) and Stephen Welsh (Living Cultures) all contributed fascinating objects, and Dmitri Logunov (Zoology/Arthropods) helped immensely with selecting, identifying and describing the natural history specimens.

While this interdisciplinary approach illuminates coral from different perspectives and creates a wealth of intriguing juxtapositions and cross-references, one could argue that focusing exclusively on any one of the disciplines or topics involved, e.g. on the science of coral conservation or on the use of coral by non-Western communities, might have been more instructive or useful. But I firmly believe in the value of visual juxtapositions: on the one hand, they capture the diversity of the material, and on the other they can inspire important questions and associations. Ideally, visitors to the exhibition would learn new things about coral, but also leave the exhibition fascinated by its beauty and strangeness. I’m convinced that, generally, combining science with art is a great way of making people care about a topic.

SP: Was the selection of the works and the other objects difficult, as the show includes works from different periods?

MEJ: I think once you realise that an exhibition like this can never be a complete, exhaustive survey, it becomes a bit easier. As my ‘expertise’ lies in contemporary and early twentieth-century art, as well as collecting and museum display from the sixteenth century onwards, selecting objects representing the use of coral by non-Western communities was a bit of a challenge.

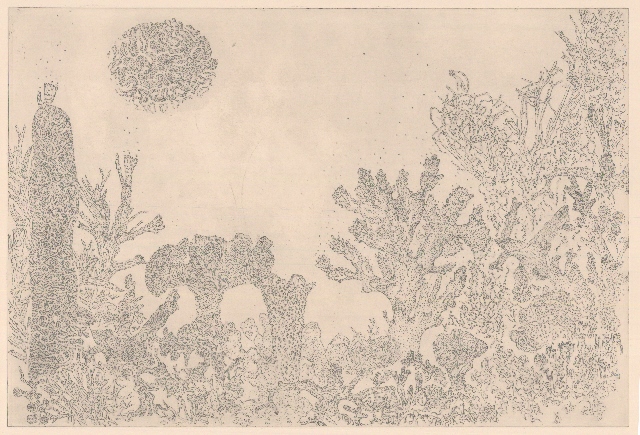

For reasons of clarity, chronology and narrative progression, I divided the exhibition into five sections early on, but increasingly found that many objects fit quite comfortably into two or even more sections. For instance, some of the dried coral specimens, such as the two red organ pipe corals, look like sculptures and therefore blur the distinction between natural and man-made. Similarly,the sea fan is deliberately placed on the wall behind Perspex within the Coral’s Decorative Appeal section, because its intricate, lace-like branching pattern is reminiscent of a work of decorative art. This deliberate probing of categories is perhaps best summarized in the exhibition by Mark Dion’s Bureau of the Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacy (2005-2013) and Gemma Anderson’s drawing Aragonite spawning under full moon (2011); while Dion’s installation questions object categories, Anderson’s work invents a new taxonomy by representing phenomena that transcend the boundaries between the three kingdoms of nature.

SP: The show juxtaposes historic and contemporary art, along with natural history specimens, textiles, jewellery, coins and other objects associated to corals. Mark Dion’s Bone Coral is based on Jacob Marperger’s early eighteenth-century treatise on cabinets of curiosities and in general the whole show, in my view, is like a ‘cabinet of curiosity.’ Do you feel that the use of corals as a subject or material frees contemporary artists, opens up new interpretations or narrows it down to its connection to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cabinets of curiosities or Surrealism?

MEJ: Yes, I think my earlier research on cabinets of curiosities and Mark Dion’s Bureau, which has existed in the Museum since 2005 and for which I commissioned a coral-related addition exclusively for the exhibition, has definitely inspired my curatorial approach; juxtaposition, the questioning of classification and the blurring of categories are all important aspects. But equally important are explanatory wall texts and labels and a certain commitment to chronology and narrative – I don’t want ‘cabinet of curiosities’ to be understood as randomness and an abandonment to personal whims.

As for the contemporary works in the exhibition, I hope that assembling them under the subject heading ‘Coral’ does not limit their possible interpretations too much. I think you are touching upon the very difficult question of how to interpret contemporary art in general, which I’m not sure I can answer. For me, the artists in the exhibition tap into coral’s rich history to highlight wider themes relevant to contemporary society, such as metamorphosis, identity, globalisation and ecology. In some cases, this association may be less straightforward; Ellen Gallagher’s work from the Watery Ecstatic series (2009), for example, can be seen as evoking the myth of the birth of coral and its subsequent association with metamorphosis in order to reconfigure notions of African-American identity based on oppression and exploitation in the context of the Atlantic slave trade. Hubert Duprat’s, Mark Dion’s and Gemma Anderson’s works are perhaps more about a questioning of categories and materials (such as ‘object’, ‘sculpture’, ‘nature’, ‘culture’, ‘organic’, ‘artificial’), but they also negotiate issues of authorship, methods of display and the creative process in general. Both Dion’s works and the Wertheim sisters’ Crochet Coral Reef reflect on collaboration and community, but also carry a distinctly environmental message. Singling out these different avenues of interpretation – in fact, any act of interpretation, including curating an exhibition – necessarily compromises the ‘openness’ of the work, but I think Walter Benjamin’s approach of ‘cutting out the rich and strange – coral and pearls’ from history and tradition or, in this case, from the complex network of intentionality and meaning that is an artwork, can be a viable method of interpretation.

SP: The Crochet Coral Reef, a project where the public is involved, has been presented in other venues. Are there any differences from the previous versions?

MEJ: The Crochet Coral Reef was initiated by Margaret and Christine Wertheim of the Institute for Figuring in Los Angeles in 2005 and has since spread to museums, galleries and communities around the world. It was originally intended as an experiment in the representation of hyperbolic space (a form of non-Euclidean geometry), but over the years it has developed associations with art, craft, ecology and conservation.

I think every satellite reef necessarily takes on a very distinct life of its own; the choice of venue is crucial, as the reef will automatically have different connotations whether displayed in an art gallery, a science centre, or a university museum. And since it is essentially a community effort, the final shape of the reef always fundamentally depends on the creative input of each single contributor.

The Manchester Satellite Reef adds an important aspect of public engagement to the exhibition; communities involved range from Museum staff and the general public to Central Manchester University Hospitals patients and members of the local craft community. The artist Lucy Burscough was responsible for organising several workshops throughout November and December 2013 – drop-in sessions where members of the public could learn how to crochet, exchange ideas for patterns, and just chat and have fun while creating something as part of a group. Other crochet sessions were held in January during Museum events, and some people even sent contributions by post from England and abroad. The installation truly mimics the diversity of a natural coral reef and it is fascinating to see how it sparks the curiosity and imagination of both contributors and visitors of all ages alike.

SP: How different will your upcoming publication Coral: A Cultural History be from the current exhibition catalogue?

MEJ: In contrast to Coral: Something Rich and Strange (Liverpool University Press), my monograph Coral: A Cultural History (Reaktion Books) will be a single-authored, more straightforward and ‘linear’ exploration of the cultural history of coral from antiquity to the present day.

One of the exciting aspects of the exhibition catalogue is, in my opinion, the fact that so many authors from different disciplines are involved, ranging from history of art and archaeology to palaeontology, ethnography, numismatics, Egyptology, history of science and biology. This variety of voices and perspectives brings a certain playfulness to the book; for instance, some more factual accounts, such as Zoology curator Dmitri Logunov’s explanation of the scientific properties of coral and of how specimens are collected and preserved, rub shoulders with more playful and imaginative contributions, such as the artist and editor of artists’ books Gerhard Theewen’s semi-fictional account of his first encounter with Mark Dion’s sculpture Blood-Coral (2011), or Carol Mavor’s wide-ranging exploration of coral’s metamorphic qualities as represented in fairy tales and ‘outsider’ art.

Another important element of the exhibition catalogue are the illustrations since a lot of the material covered is, quite simply, visually compelling. Generally, I would like both publications to be a mix of history and theory, an account of how coral has been used and represented in natural history and art, addressed to an audience that is not exclusively academic.

Coral: Something Rich and Strange continues at Manchester Museum until 16 March 2013.

Steve Pantazis is a contributing editor for Corridor 8 Online, independent art historian, writer, associate editor for Versita Publishing in the field of Arts, Music and Architecture.

Published 07.02.2014 by Lauren Velvick in Interviews

1,978 words