I’m at the Portico library, a former members-only library in central Manchester, for their current exhibition How to Read a Book from artist-writer Stephen Emmerson. There’s a section of the exhibition displaying what Emmerson calls his ‘Poetry Wholes’ (2014/2025). Sheets of opaque red perspex with simple shapes cut out of them such as, in one, a triangle, and in another a narrow side up rectangle. These templates are intended to be placed over pages of text, with the words which then become visible through the holes to be considered as poems. It’s a beautifully simple idea, and one of the first ways that Emmerson suggests how to read a book. I find myself musing on the relationship between the ‘whole’ and the ‘hole’, what the concept of ‘wholeness’ even means, and marvelling at the demystificatory, democratic impulse of the pieces, how they show that poetic manufacture need not be some mysterious process known only to a select few, and show instead how the making of poems can be an activity open to everyone. I’m overjoyed to find, a little bit further on in the exhibition, an open box of Emmerson’s ‘Poetry Wholes’ that attendees can try themselves.

This democratic impulse makes perfect sense within the exhibition’s setting, as the Portico Library finds itself currently in the middle of its Portico Reunited project. The library is trying to raise money to reclaim the ground floor of the building (currently housing a pub) in order to create a bookshop and kitchen there, and to increase accessibility so that all members of the community can make use of and enjoy the collections held within. Alongside Emmerson asking how to read a book then, it seems the Portico – with the questions it’s asking of itself as part of the Reunited project – is also asking how to read a library: what does a library want to be in the twenty-first century? How does it stay relevant? How does it keep its collections alive for future generations?

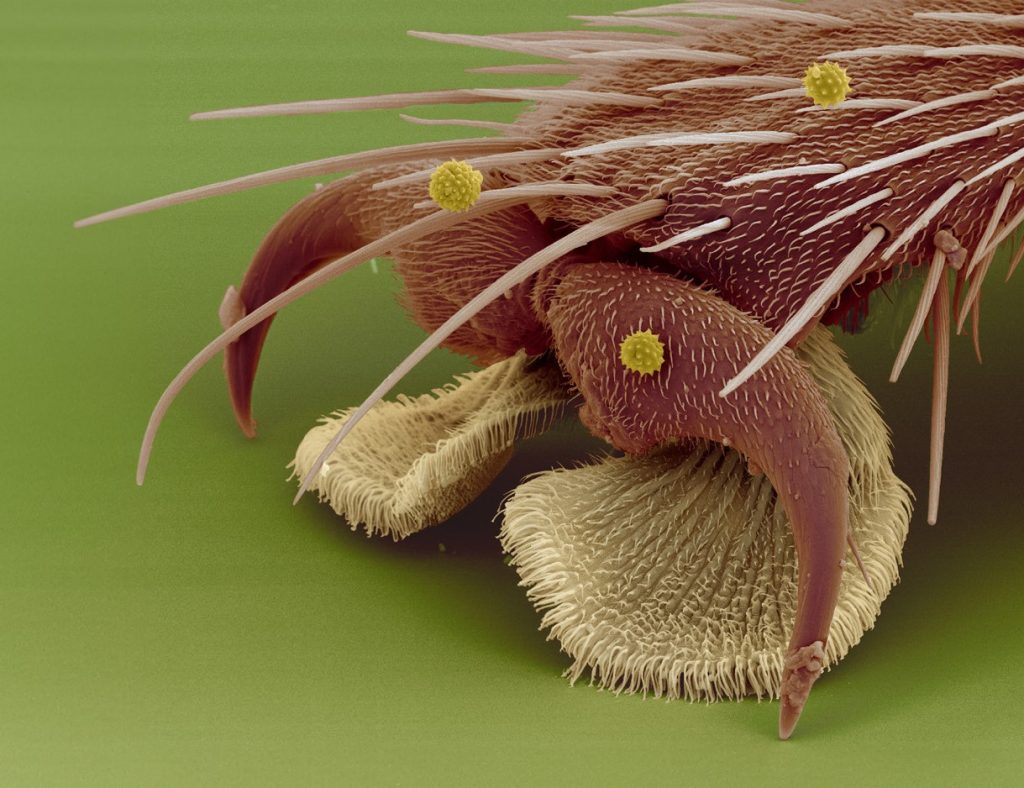

What does a library do when it finds evidence of books that have been damaged by beetle larvae and paper mites (aka bookworms)? Well, if you’re Stephen Emmerson you have the rather amazing idea of tracing the shape of the damage, and using these shapes as the basis for templates similar to the ‘Poetry Wholes’ mentioned above. In this piece, ‘Wormholes’ (2025), we’re again looking at shapes cut out of pieces of perspex, this time black perspex. Rather than the simple geometric shapes of before though, we’re now looking at and through Rorschach-test style holes. In this section of the exhibition we see Emmerson’s interest in change and transformation emerge. He’s showing us how books, as material objects, can change over time when subjected to, for instance, the attention of pesky little worms: what was whole on the day of publication no longer is, having become an object riddled with holes. But perhaps he’s also asking us to think about the insides of books – the knowledge, thought and learning contained within a book’s pages – and asking us to consider how ideas themselves might seem to change, in terms of their meaning and value, depending on the different perspectives and lenses through which they’re being viewed.

This theme of change recurs in ‘The Book Farm’ (2025) a series of beautifully abstract photographs that, from a distance, are all colours, patterns and shapes, which, the nearer you get to them, slowly reveal themselves to be photographs of books deliberately left outside ‘beneath fungus…at the base of rotting trees, in the long grass… under logs and beside rabbit holes’, as the exhibition wall text puts it. Books which have changed shape, changed colour, changed density due to exposure to both the elements and time. Changes which exhibition curator Apapat Jai-in Glynn explains to me are all occurring to the Portico’s own collection, just at – thankfully – a much, much slower rate.

Besides the beauty of these images there’s also a real humour at play as we notice one of the books left outside to rot is a copy of Rivkin and Ryan’s Literary Theory: An Anthology, first published in 1998. Emmerson seems to be saying here, that for him, academic literary theory is about as useful as a discarded copy of yesterday’s Metro newspaper and showing us, at the same time, his own literary theory of action and doing, with words as material objects. If we listen carefully we can hear the Portico responding to this piece in enthusiastic agreement, letting us know that the library also believes books are not sacred items, that books are supposed to be actively engaged with and used.

Emmerson’s directions in How to Read a Book involve reminding us that reading is a physical activity, as well as something we do with our eyes, mind and emotions. We see this in the act of picking up and putting the ‘Poetry Wholes’, or ‘Wormholes’, over the page, manually adjusting their positioning until we’re happy with the results. We see this, as well, in the act of selecting a literary theory book from off the shelf, taking it outside and leaving it in nature, for nature to do what it must with it. Nowhere more clearly, perhaps, do we see the physicality of reading than in Emmerson’s short film ‘Pett Level’ (2024). The film involves a walk around the south coast and is introduced by a brief on-screen text explaining that ‘since 2018 100s of people have died trying to cross the channel’, a reference to the number of people who have tragically lost their lives seeking refuge in UK, while trying to flee war, persecution and famine in their countries of birth. In the film we see old concrete structures known as acoustic mirrors, a pre-radar form of early warning system – huge, imposing and immobile, contrasting starkly with the unceasing movement of nature, the flowers and grasses alive in the breeze. Emmerson is represented in the film by his voice alone, reciting the lines of a poem. What’s the book, here, we might wonder. Well, of course, it’s nature, it’s the world. And the only way we’re going to be able to read this particular book is if we get ourselves out into it.

‘Pett Level’ is a film of memory and ghosts. Besides commemorating those who died trying to cross the channel, the film is also heavy with the presence of the soldiers who patrolled the coast trying to read and interpret the sounds being picked up by the instruments represented in the film. Emmerson too, by being both not in the film, and in it, becomes a kind of ghost himself. All of which resonates perfectly within the confines of the Portico when we think of its own ghosts. From the spirit of Tinsley Pratt, twice Portico librarian, who curator Jai-in Glynn tells me was reputed to have died in mysterious circumstances, to the bust of notable early member Mr Gaskell, to the faces of Shakespeare and Milton staring across at each other from either side of the ceiling’s magnificent dome. And of course, alongside all these famous figures are the ghosts of the library’s past patrons themselves. People who have spent time in the place head-bowed and silent, consulting the periodicals and books, the marks of some of these patrons still visible from decades earlier in the damage done to items in the collection. The Portico, today, deliberately opts to show books on its shelves exhibiting evidence of wear and tear, believing it’s important to show how collections were used then, and how the Portico, as contemporary custodians, treat the collection today to pass on to future generations.

The damage done to books by use and time offers Emmerson yet another way to read books. In a section at the start of the exhibition, the titular ‘How to Read a Book’ (2025) section, he takes the rules of palmistry, involving interpreting the lines and wrinkles of hands, to try to decode the creases, bends and folds of much used paperback books. Open a paperback to approximately the middle, he instructs, place it pages-down on a flat surface. Trace the lines and marks from the books back, spine and cover. Emmerson then provides us with a key to make sense of the marks we’ve copied onto our sheet of paper. This section evidences a creative mind at play, someone with a great sense of humour, who is showing us, here, that yet another way of reading a book involves communing with spirits and ghosts of the book’s past readers.

However, the dominant spirit of the exhibition is undoubtedly John Milton. He’s present not just in image at the side of the dome, he’s also there in Emmerson’s piece ‘Milton’ (2025). A small card on display in this section contains a quote from Milton detailing his view that books contain within them ‘the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them’ and that this essence is contained within books ‘as in a vial’. So, of course, this has prompted Emmerson to soak a copy of Milton’s prose writings in a jar, and collect the water containing this essence of their author into vials, which we see displayed besides the quote and a photograph of the jar full of water containing the book. Returning to the question of what it means to read a book then, how about trying to read a book literally, as Emmerson seems to have done here with Milton’s quote, because it’s this literality that’s resulted in this wonderfully amusing piece.

It’s a piece in conversation with an edition of Milton’s own Paradise Lost in the next case along. The fourth edition, but the first illustrated edition, displayed within a UV filtered glass case on a tailor-made paper cradle, kept at the angle that best supports the book and its condition. The book’s care and condition are being closely monitored throughout the duration of it being shown. Milton and Emmerson’s works, here, offer us a beautiful example of how thought from one age talks to, and interacts with, thought from another age. Apropos this section, and the exhibition as a whole, curator Jai-in Glynn writes to me after my visit to share some final thoughts: ‘Don’t let the age of an old book or ancient heritage be a barrier for you to interpret them. Rather, use the fact that it is old and ancient to fuel you to ask more questions, dig deeper to understand why people before us thought it was “set in stone” and turn it into a mould-able form and have fun with it. Make it relevant to you, to us. Heritage is not about setting things in stone. It is alive and fluid because we keep asking, playing, and reinterpreting it!’

I’ve already mentioned the sense of humour this exhibition has, but for me the biggest laugh comes at the piece ‘Sheep Poem’ (2025). Here we see a photograph of a sheep in a field, a glass bottle of some hard-to-identify matter, and a printed explanation stating: ‘a poem was printed on rice paper/ and fed to the sheep in the photograph/ a few days later I collected a sample of/ the sheep’s translation’.

*

On 27 November there’s a reading taking place within the library featuring Stephen Emmerson and guests. For the reading, Emmerson is bringing with him a new artwork he’s created from items collected by the library over the years. And as we’ve just seen thought and learning in flux – both within the exhibition and in the library – this show is also refusing to be set in stone, it’ll be assuming a slightly altered form after the 27th. My recommendation is to see it before that date and after. Take whatever opportunities you can to visit this beautiful building, take inspiration from the huge variety of stories within and go forward and write your own stories.

Stephen Emmerson: How to Read a Book, The Portico, Manchester, 3 October 2025 – 14 March 2026.

Richard Barrett has been in and around the Manchester poetry scene for more years than he can remember.

This review is supported by The Portico.

Published 19.11.2025 by Jazmine Linklater in Reviews

2,160 words