Those familiar with Hull’s development over the past twenty years will recognise the construction of The Deep as a kind of temporal marker for when money started trickling back into the region. In its own words, The Deep ‘opened in 2002, in what was then one of the most deprived and unfashionable cities in England’ – five years before even the arrival of St Stephens shopping centre, which has become a somewhat hyper-capitalist symbol of Hull’s revival.

A centre dedicated to marine life was an auspicious choice to herald the resurgence of Hull as a centre of culture and regeneration in the East Riding, as the region’s stagnation in the late twentieth century had largely been propelled by the decline of its fishing industry. As well as functioning as an aquarium The Deep carries out research and conservation activity, which forms a large part of its public programme. The organisation’s aim is ‘to help raise public awareness of marine conservation issues of national and global significance’ – including the environmental legacy of industrialised fishing in which Hull has played a significant part.

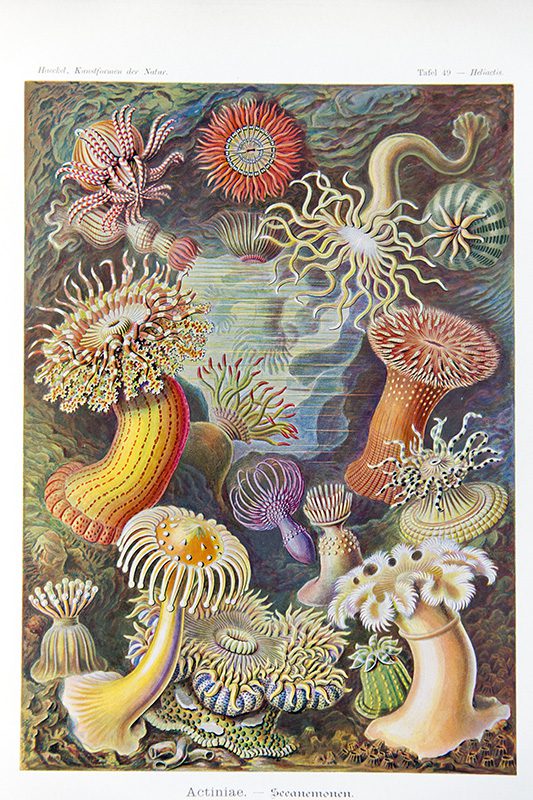

Images of marine life forms drawn by Ernst Haeckel (1834 – 1919) are currently on view in The Deep’s ‘exhibition space’ – a wider-than-usual corridor leading to the entrance of the aquarium itself. Haeckel was a prolific German scientist, philosopher and artist, whose contribution to biology is arguably paralleled by only Charles Darwin. In his phenomenally wide-ranging practice Haeckel discovered, described and named thousands of new species, mapped a genealogical system relating all forms of life and is credited with coining many biological terms including ‘ecology’ and ‘stem cell’.

Haeckel’s colourful, almost lurid images were originally published in the artist’s 10-volume ‘Forms of Nature’: an early (and rather epic) example of artists’ publishing. A naturalist only in the scientific sense, Haeckel’s philosophy was profoundly religious. His detailed, super-natural images speak to a life-long fascination and wonder at the teeming diversity of life forms in the world, and their intricacy. His thoughts linking Darwin’s evolutionary theory to religion are well documented, and Haeckel was significant in establishing Darwin’s theory of natural selection as an accepted worldview in Germany (On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, when Haeckel was 25).

Particularly relevant to Hull’s maritime history is ‘Plate 23’ (1904), Haeckel’s delicately rendered survey of the phylum Bryozoa – ‘moss animals’ or ‘pond fairies’ – in various stages of development. Exposure to one variation of this life form (the innocuous-sounding Sea Chervil) causes the crippling skin condition ‘Dogger Bank itch’ in seamen, so named after the shallow spot in the North Sea off the east coast of Yorkshire where fish – and the offending Chervil – are plentiful. The Dogger Bank is soon to host a new off-shore wind farm, heralded as the creator of hundreds of jobs in Yorkshire and Humberside: the region’s fortunes seemingly remain tied to the North Sea.

Haeckel, like Hull, remains a mass of contradictions. His legacy of exquisite images and significantly greatened understanding of life on earth must always be contrasted with his harmful contribution to the now-discredited theories of ‘social Darwinism’, which informed so much Nazi and Fascist ideology in the early twentieth century. Similarly, Hull, as a maritime city, has historically been a major proponent of the UK’s imperial and colonial expansion, and yet fostered unique radical movements for the abolishment of slavery and protection of civil liberties. Complex legacies abound at sea and on land, and the struggle for survival continues.

Marine Art: Ernst Haeckel, The Deep, Hull, 1 September 2017 – 31 October 2017

Jay Drinkall is a writer and editor based in the UK.

Published 13.10.2017 by Elspeth Mitchell in Reviews

604 words