Stone-cold conceptual artworks are pressed against the edges of Bonington Gallery. The works of London-based artist Motunrayo Akinola (b. 1992)—some softly illuminated—are positioned in four distinct places in the dimly lit cuboid room. This body of drawing, installation and sound has a sense of performative crudeness. Even more so, there is a geometric crudeness in how the pieces are displayed. At the back of the gallery, ‘Tomorrow’ (2025) comprises lines of archive boxes containing the paper-based archives of the university gallery from between 1989 and 2005. They are placed directly on the floor in almost military formation, queued towards a spotlit, black-curtained exit as if eager to leave. There is nothing hopeful about the stiff, dark grey materiality of these objects, which exhibit the uniformity typical of a corporate environment or bureaucratic public administration. One uninteresting observation from this installation is that the folders may prompt spectators to recognise an obvious fact: they are in a university. A modern-day university is the near-perfect blend of two doctrines that together might make someone recoil a little (okay, a lot): capitalism and bureaucracy. Is there a combination that feels more emotionally cold?

The artwork ‘Tomorrow’ is the product of Akinola being selected for the 13th Postgraduate Residency programme at South London Gallery (SLG), in partnership with Bonington Gallery. The exhibition was first held at SLG and ended in June 2024, moving to Bonington with changes, or an ‘expansion’. After a site visit to Nottingham, the boxes (or ‘objects’—the contents seemingly inconsequential to the artist) were retrieved from storage and placed in the gallery. The approach appears to be an effort to create site-specific art, or to enhance the site-specific relevance of the show’s second iteration. Maybe it’s not even a conscious attempt, as the work and its process seem psychologically emblematic of the nonunique capitalist condition of art schooling where the office cubicle—Robert Propst’s exploited ‘Action Office II’—and allocated studio space have become indistinguishable. Here, Martine Syms’s art-school-insider satire ‘The African Desperate’ (2022) also comes to mind. Sym’s film chronicles the graduation day of MFA artist Palace Bryant, portrayed by Diamond Stingily. ‘Hunter-gatherer sculpture here’, ‘found materials there’, ‘appropriated photography’ says the lecturer. Palace’s final showcase features an overturned bucket and a piece of Himalayan rock salt, resembling the efforts of an overeager set designer more than those of a burgeoning contemporary artist, as critic Pierre d’Alancaisez writes in a review of the film for ArtReview. This chimes with the description of the black curtains of Akinola’s work in the exhibition text, which are said to be ‘an entry/exit point to a stage or otherworldly threshold’. ‘Everybody is trying so hard to look like they’re not trying that they nearly succeed’, says d’Alancaisez, commenting on the characters in ‘The African Desperate’.

Whilst on the surface equally cold and despairing, ‘Movement 16’ (2025) handles the artmaking process of site-specifying more sensitively. Part of an existing series, the painterly drawing in charcoal and gesso was produced through a private performance in which Akinola walked around the empty gallery at the beginning of the installation period, chanting the words ‘black teeth’. Using footage from this performance, locations where Akinola spoke the phrase were overlaid onto a technical plan of the gallery and its surrounding areas. The disintegrative nature of the serial is the investigation. It brings to mind a piece by American artist Glenn Ligon with a similarly formatted title, ‘Figure #58’ (2010)—a work made of acrylic, silkscreen and coal dust on canvas. Part of a series of fifty unique silkscreens, each figure in Ligon’s series is an abstracted self-portrait of the artist. Inky coal shapes simultaneously seeping into and secreting from the fabric emerge like jagged teeth. ‘Figure #58’ and ‘Movement 16’ are arguably outcomes of a long-term compulsion to burn through the canvas, psychologically speaking. Thick and chalky substances like silkscreen ink, coal, charcoal, gesso and oil stick explore their own existence.

In different ways, both Akinola and Ligon contend with the notion of the singular—a phrase, a single line, a single thread of language—through the lens of seriality. I see the repetition of charcoaled teeth receding into the linen of Akinola’s piece as a pictographic take on ‘writing lines’, a punishment handed out to misbehaving students. As a form of discipline, an individual copies a specific sentence onto a standard sheet of paper or a chalkboard as many times as the person administering the punishment deems necessary. The written sentence often relates to the reason for the punishment. Darkness, in its various meanings, exists within the canvas, hidden yet not entirely out of sight. Akinola’s verbalisations transform into pictorial outlines—the charcoal conceals traces, or ‘teeth marks’, left as remnants of the performance.

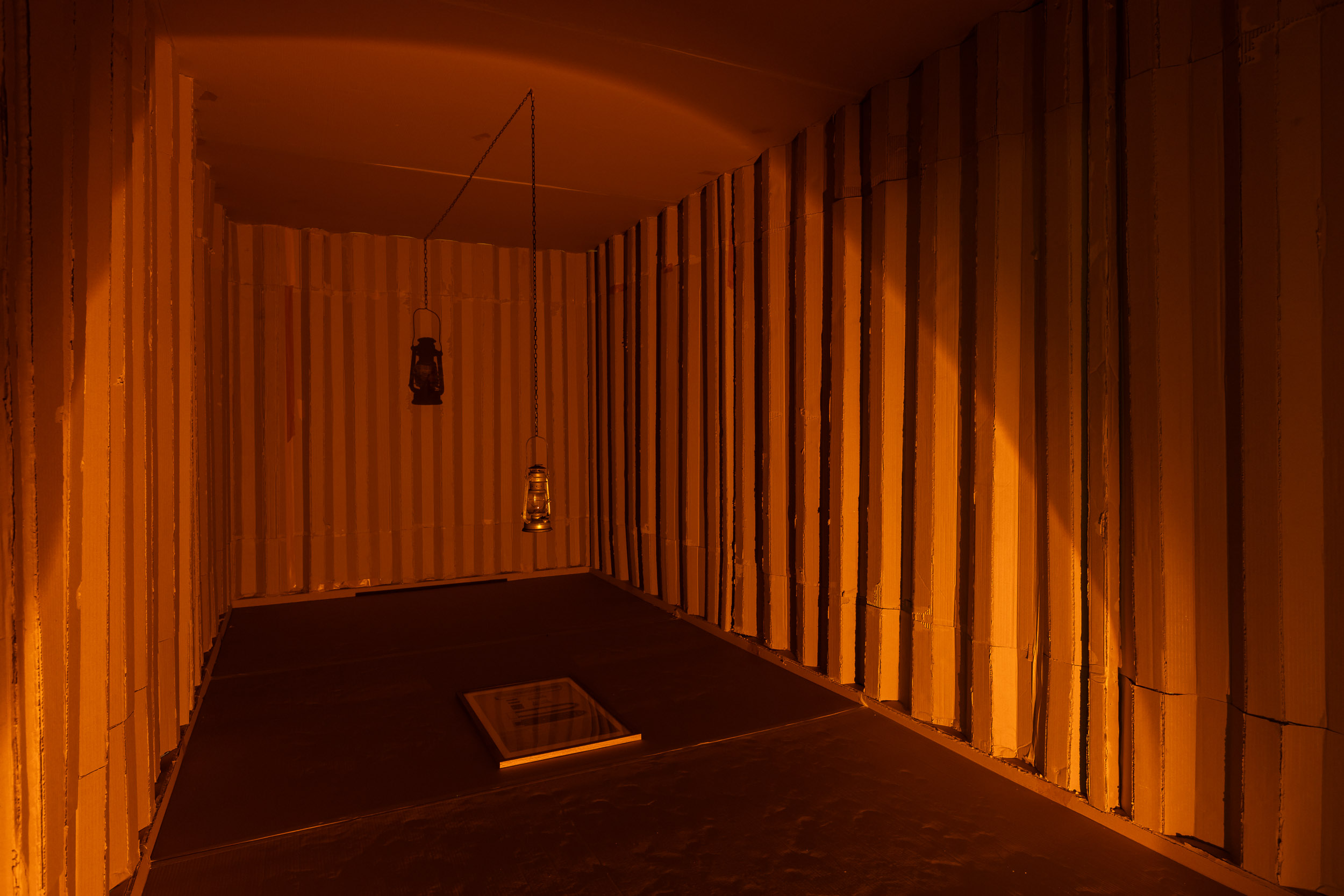

The traces deriving from repeated layers of marks and infill, along with cascades of charcoal dust, form a type of ‘leakage’ on the linen. The material messiness created through physical performance is not dissimilar to Akinola’s elder, artist Jade de Montserrat, whose care practice attends to the tactile and sensory qualities of language. Akin to Montserrat, attentiveness is present in how the drawing deals directly yet discreetly with the body, unlike the illustrative nature of the image of the slave ship ‘Brooks’ (launched in 1781), used directly in Akinola’s ‘Cargo’ (2024). The horizontal placement of the Brooks poster directly on the floor of a sizeable cardboard shipping container is fascinating. And even more arresting if understood as an intimate encounter with how bodies lay flat in eighteenth-century slave cargo ships. The slave ship illustration, created in 1788 by the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in Britain, is a key visual symbol that has played a potent role in shaping African diasporic culture and identity. Akinola’s piece joins a long lineage of the image’s usage as an ‘Afrotrope’ (a term coined by art historians Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson), such as in Binta Diaw’s ‘Chorus of Soil’ (2023) and Keith Piper’s ‘Go West Young Man’ (1987), but is arguably less skilful.

However, the impression that ‘Cargo’ gives is less simply about migrant stories and more about the violent use of architecture and the architectonics of (sensory) deprivation. We don’t know the stories of the people—stripped of identity—rendered in diagrammatic form in the Brooks illustration. Instead, the use of the highly charged image produces a conjuncture that time-travels between narratives of historical slavery and contemporary human trafficking. The work draws connections between the architecture of the modern cargo container—think Albert Pintó’s fictional Netflix thriller Nowhere (2023) and the non-fictional cases of Irish police discovering people in shipping containers at the port of County Wexford, as recently as January this year—and the historic slave ship. If the viewer follows this painful thread of thought and registers how they feel in the installation, the politics of solitary confinement and carcerality may also come to mind. Cramped together in darkness, with little airflow and sanitation—if your freedom is curtailed and denied, your enslavement pathologized (as in Samuel Adolphus Cartwright’s dehumanising Drapetomania), the only thing you may have left is despair. Rather than the artist’s intentions, this reading might be closer to what it means for ‘knees to kiss the ground’.

Jade Foster is a curator and art historian previously based in Nottingham, in the process of moving to Yarm, North Yorkshire.

Motunrayo Akinola: Knees Kiss Ground is on at Bonington Gallery, Nottingham Trent University, from 18 Jan 2025 – 08 Mar 2025.

This review is supported by Bonington Gallery.

Published 03.03.2025 by Benjamin Barra in Reviews

1,283 words