The seats in the exhibition space at Birkenhead’s Williamson Art Gallery bear small polished brass plaques, in the manner of memorial benches commemorating a late loved one in a place that was meaningful to them. Here, in Who Wants Flowers When They Are Dead?, they are engraved with facts and statistics about grief. Curated by Lizz Brady – founder of Broken Grey Wires, an organisation creating projects that centre artists with mental health challenges, disabilities and neurodivergence – Who Wants Flowers When They Are Dead? is a group exhibition of mostly recent artworks in a variety of media, tackling themes of loss, mourning and remembrance. The curator’s note in the exhibition’s catalogue states that the show is born from the grief she has lived with since her dad died five years ago, and a need to try and understand this capsizing emotion.

Loss is something that most people will experience – so goes the idiom about death and taxes being the only certainties in life – but in the UK we are not very good at talking about it, with a third of people, according to one of the bench plaques, admitting they don’t speak about their grief due to the worry of upsetting others. The benches that bear these brass plates have been created from the flat, rather uninviting forms of the gallery’s regular seating. These have been reworked by local artist duo Paddy Gould and Roxy Topia into hybrid creations, with the varnished wooden backs and arms of park benches, making them more accessible, and turning them into places where people might actually want to sit awhile, indicating the close attention to visitors’ experiences and access needs that permeates the exhibition. The first thing you encounter on entering the gallery is a pegboard offering different ways to navigate the show including activity cards for engaging with artworks, and headphones for a gentler sensory experience, available upfront to anyone who might like or need them.

The durational nature of grief is touched on throughout the exhibition; the way it seems to change the fabric of a person, clinging to the bereaved; its ebb and crashing flow. ‘Light on the darkest days’ (2023) by Scarborough-based artist Jacqui Barrowcliffe is an artwork consisting of hundreds of small oblong cards, tinted various shades of blue, like paint swatches, displayed in a grid on the gallery wall. They are cyanotype prints, which change colour when exposed to sunlight. Instead of capturing an image, these prints are a record of climate and time passed, ranging from barely coloured to inky navy. They have been created during daily walks during which the artist would pause on a bench and look out to sea, a ritual to seek moments of peace while wrestling with grief. Displayed together, they are a visual document of this period in the artist’s life. Barrowcliffe invites the viewer into this setting, placing a bench in front of the prints, arranged by shade to recreate the blue horizon.

Multidisciplinary artist Jessica Loveday also turns to nature to try and unpick grief, in the wake of the loss of her mother. In her poetic film ‘In this tidal place’ (2025), Loveday walks across a salt marsh carrying fabric sculptures, printed with arcane blue shapes that reference a family heirloom. These are displayed in the gallery, but come alive on the adjacent screen as they move with the breeze across the flats. Steadily, meditatively, the artist narrates her connection to the land and how its timeless qualities allow space for memories to surface. The camera lingers on the rippling tidal pools and blowing grasses of this semi-solid landscape. Addressing her mother directly, Loveday reflects that when she is here, ‘the boundary between us is thinner’.

A pair of disquieting short films on monitors from Cuban-American performance artist and sculptor Ana Mendieta’s ‘Silueta’ series demonstrates the late artist’s physical and spiritual connection to the land. These are the only pre-21st century works in the exhibition, pointing to her influence on later generations. The shape of Mendieta’s body, arms raised to the heavens, is forged into the landscape through ritualistic performances; in ‘Anima, Silueta De Cohetes (Firework Piece)’ (1976) it stands, picked out in fireworks that burn red against the night sky, while in ‘Alma Silueta en Fuego (Sileuta de Cenizas)’ (1975) it lies flat, a white shroud that catches alight before it is rapidly engulfed in flames, conjuring the presence of something ancient, powerful and unnerving.

In ‘Earthing Up Ghosts’ (2025), socially engaged artist Emily Simpson uses her own creative process to hold a space for others. This is another work rooted in nature, here the more domestic environment of her father’s allotment, a space she continued to care for following his death. A table in the gallery space is draped in a patchwork tablecloth that is stitched with panels in earthy greens and browns. These depict the shapes of leaves, seeds and tendrils, and phrases such as ‘tending to grief’, connecting the processes of gardening and dealing with bereavement. The table is intended as a communal space, open to conversations around grieving; Simpson will facilitate a pickling workshop during the exhibition’s run, using practical skills as a tool to unlock feelings that can be difficult to share. Offering the choice of how much or little to participate, and opening a way in, is in keeping with the exhibition’s ethos.

Inevitably, and perhaps by design, visiting the exhibition stirs thoughts of personal losses. I recalled my mum, who died when I was fourteen; she was forty-eight, and I loved her very much. It’s rare that I see depictions of grief that chime with my own experiences. The raw hurt that pours freely in films and TV series sat dumb as a stone for me; I hated the extra attention at school and was desperate for things to be normal. I put on some headphones to watch filmmaker Gurinder Kumar’s ‘What makes you?’ (2022-25), displayed on a scratched up little TV-video combi that takes me back to my teens. It is a work about vulnerability, in which people on the streets give vox pop interviews on their fears, struggles, loves, hopes and losses; an adjacent grid of polaroid portraits is annotated with things that make the sitters happy or sad. I joined the video as two teenage boys in turn talked about the death of family members, and it struck me that both began by saying they’d never really talked about this before, their experiences of loss told like confessions.

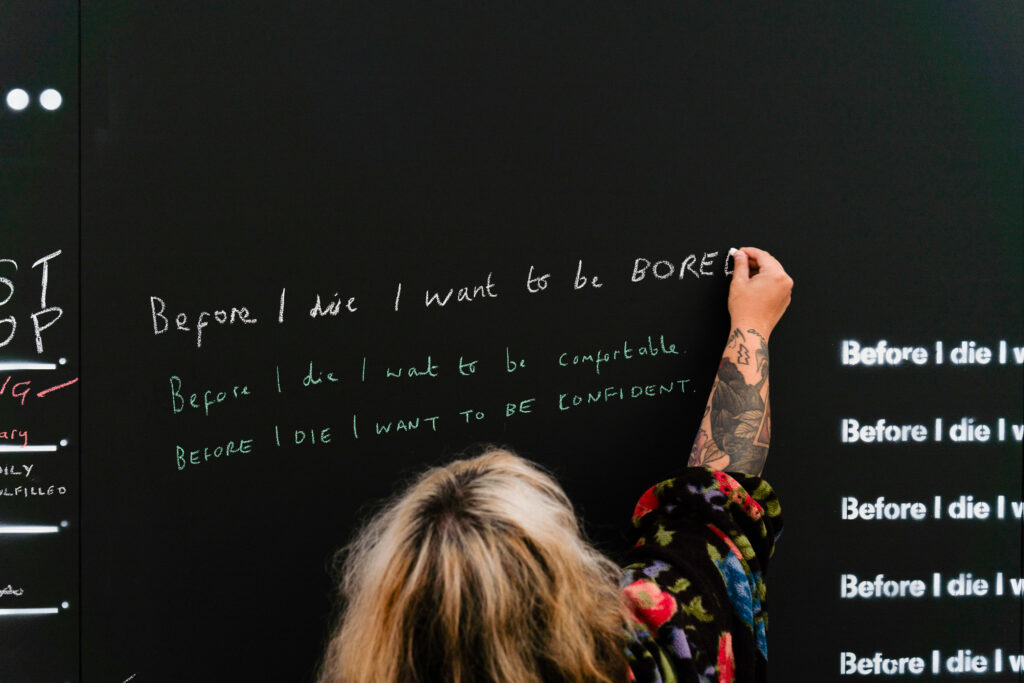

US-based artist Candy Chang encourages visitors to share a little of their own inner lives with an iteration of ‘Before I Die’ (2011-present), a participatory installation that has been recreated thousands of times by different communities around the world since its inception. Here it is presented as a square of four chalkboard walls, inviting members of the public to complete the sentence, ‘Before I die I want to ___’, by writing directly onto the walls. This confrontation with the certainty of mortality elicits a range of responses, from the anarchic (‘tell everyone I hate to fack off!’) to the poignant (‘see my son’), that will change and grow during the duration of the exhibition. The sharing of feelings is made visible and simple to participate in, however deep the visitor wishes to go. Inside the chalkboard walls is the exhibition’s Comfort Zone, a lamp-lit area with soft furnishings and shelves of zines, designed as a space for visitors to take some time out. I sat in an armchair and read a poem in one of the zines while my toddler ate a rice cake; an uncomplicated, low-pressure moment of niceness.

For me, the difficult feelings associated with grief don’t come at expected moments; birthdays and anniversaries come and go, and sometimes I forget them and feel bad afterwards. But then I’ll feel an ache like hunger out of the blue; it’s a feeling I get sometimes in our local chemist / purveyor of fancy goods, something in the knick knacks in the window. Jasleen Kaur’s ‘Highs’ (2016), a series of works on paper by last year’s Turner Prize winner, captures something of this, the way an object can spark complex emotions. Yellowing pages of a 1990 copy of Auto Trader magazine recall a childhood in which cars featured heavily, a recurring symbol in family photographs and memories. The pages are framed and overlaid with silhouettes of mountains cut from marbled paper, referencing a Sikh pilgrimage to the Himalayas that Kaur took with her father, in collages that treat both ordinary and extraordinary memories with equal weight.

Curator Lizz Brady’s sculpture ‘Doors falling off their hinges are often caused by loose screws’ (2025) is a three-dimensional drawing of the floorplan of her old family dining room, created as a metal framework. At one end an interior door balances precariously, hinges hanging loose, its white paint faintly grubby with everyday homelife. The work recalls a memory from the artist’s childhood: her father’s appearance at the moment when she and her sister broke their dining room door, the kind of small drama that becomes family legend. The title of Johnny Thunders’ 1978 song ‘You Can’t Put Your Arms Around a Memory’ drifted into my head; Brady’s work feels like a defiance of that notion, making an intangible memory into solid metal and wood, graspable, back here in the present. A gorgeous pair of works by Glasgow-based painter Antony Connelly, ‘Nana and Pop’ and ‘Gran and Papa’ (both 2025), also explores family memories, and the ways in which both sets of grandparents shaped his childhood. His paintings are assemblages of styles and subjects; scenes from photo albums, such as a black-and-white picture of a victorious football team, are rendered realistically, while a classic red and yellow ride-in toy car is drawn in childlike lines. Cartoon characters, a fragment of a staircase, a domino, a can of lager, all float on the canvas, a jumble of scrappy, affectionate memories.

Grief isn’t only quiet remembrance, however. Sometimes it rages, particularly when a loss feels unjust; a life cut abruptly short, or precious time filled with suffering. The exhibition’s title, Who Wants Flowers When They Are Dead?, snaps back at a perception of softening the starkness of death. Artist and writer Dolly Sen’s ‘The Fabric of our Fury’ (2025) is a large-scale collaborative textile work inspired by the embroideries of Lorina Bulwer, a woman incarcerated as a ‘lunatic’ at Great Yarmouth Workhouse for a number of years until her death in 1912. There she created lengthy needlework samplers, in capital letters and devoid of punctuation, filled with protest, anger and indignation. For this homage to Bulwer, which hangs in brightly coloured patchwork lengths down the gallery walls, Sen collaborated with more than twenty fellow women needleworkers to voice fury through stitched texts at contemporary injustices, many associated with disability and ill health: the intrinsic failings of PIP, ineffective politicians, and seething frustration at being patronised. Amy Mizrahi, a painter based in Liverpool and Manchester, explores her personal experiences of illness in ‘A Little Bird Told Me So’ (2025), a surreal self-portrait inspired by a dream. Features such as the bird on her shoulder, and the wooden box of jewel-coloured fish on the table, are painted with thin, multicoloured lines like a carefully worked illustration, giving the scene a fairytale quality. In the painting she sits naked; part of her left leg lies next to her on the floor, replaced at the knee with a fish. In her accompanying text, Mizrahi refers to this transformation as a kind of ‘healing’, coming to terms with the loss of her former self through chronic illness.

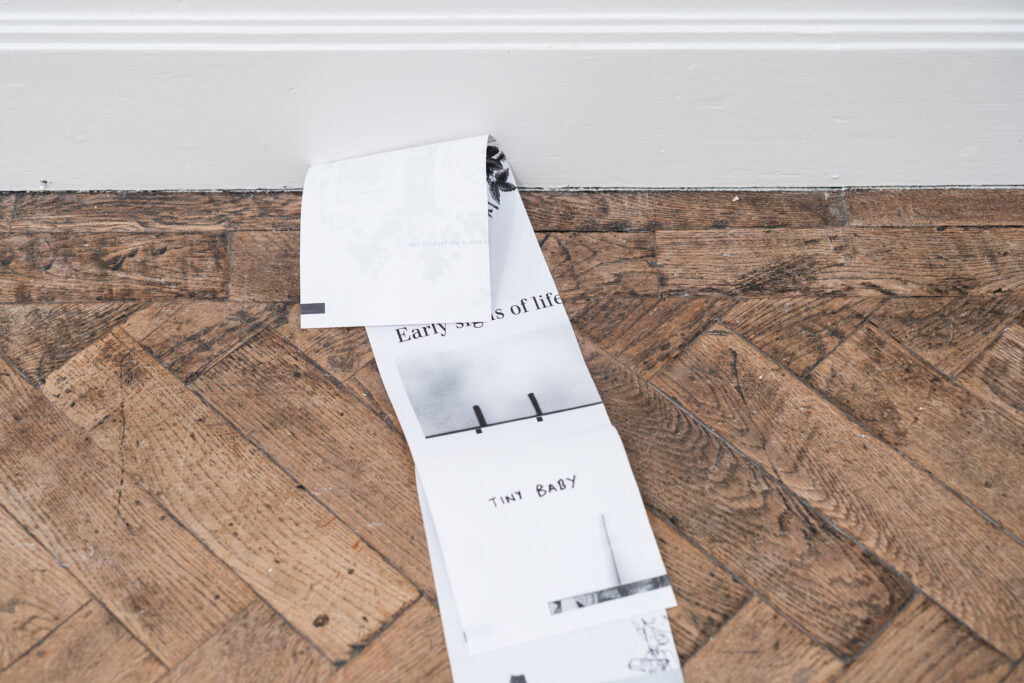

The personal loss that can accompany motherhood is explored in a number of artworks in the show; an experience usually associated with new life can signify a seismic loss of self, and subsequent rebirth, for new mothers. Artist and mother Sophie New’s installation ‘The First, Second and Third Stages of Labour’ (2025) presents a CTG machine, used to monitor baby and mother during labour. Rather than heartbeat and contraction data, its paper feed, trailing onto the floor, is filled with sketches depicting the overwhelming first days of motherhood: nappy reports, miniature milk bottles, feeding schedules and so much unsolicited advice. New’s giant sculptural tower of toast, ‘The Fourth Stage of Labour’ (2025), stands as a monument to the fabled regenerative properties of the stack of NHS buttered white toast offered to many new mothers. Fellow artist-mother Marcelina Amelia’s ‘Oxytocin Killed My Shoes’ (2024) is a memorial to the footwear that no longer fit her after childbirth; chemical changes in pregnancy relax the foot’s structure, which often never recovers. Her boots and shoes are captured in monochrome photographs and transferred to tiny oval porcelain plates. These are mounted on the wall like portrait miniatures; the items memorialised before, we are told in the catalogue text, they were ritually buried in the earth by the artist.

Who Wants Flowers When They Are Dead? explores grief in all its multiplicity and knottiness, much more than there is space to tell here. While taking in the artworks, I thought about how we are encouraged to ‘sit with’ our feelings these days; a concept that was alien to my teenage years, and something that definitely takes practice. The exhibition offers a space for this; lots of actual, accessible sitting space in which to dwell, but also multi-faceted perspectives, and a choice of ways in which to engage. It handles the perplexing subject of grief with sensitivity and curiosity, offering no easy answers where there are none, but laying it out carefully for contemplation, and maybe even a conversation.

Denise Courcoux is a writer based in New Brighton.

Who Wants Flowers When They Are Dead?, Williamson Art Gallery and Museum, Birkenhead, 25 July – 13 September 2025.

This review was supported by Broken Grey Wires

Published 14.08.2025 by Natalie Hughes in Reviews

2,371 words