Matter in the form of rain leaches from a January sky the colour of lead as I make my way along the wet streets of Beeston, south Leeds. I’m on my way to artist-led space BasementArtsProject, which has been in residence in the basement of Bruce Davies’ terraced home for the past fifteen years. I’m here to see Ethereal Matter, a group show that brings together work by nine students on the MA Fine Art course at Leeds Beckett University.

To step into the kitchen of this domestic setting is to find warm and friendly refuge from the dreariness outside and to plunge into conversations on where art begins and ends, or whether such distinctions matter. Hanging from a washing line strung from one side of the room to the other is a series of cyanotypes by Abbie Bruff, titled ‘Things We’re All Too Young to Know’ (2025). Printed on cotton, they preside like banners over a kitchen table strewn with everyday signs of family life and creative labour: coffee paraphernalia, a bottle of shower gel, a laptop, a notebook. Bruff’s banners bear quiet, intimate photographs of her friends, ‘the people I love’ as the artist says, caught in moments of repose and introspection as they recline on a bed or prepare to dress for a night out. The deep Prussian blue of the cyanotype process, with its melancholy overtones, sits happily with this form of image-making.

The rest of the works are installed across two interlinked rooms in the basement and in a recess at the foot of the steep steps that are its only means of access. In the first room, Lorna Buckley’s ‘Ballet’ (2025) presents a logical stepping off point from Bruff’s prints upstairs. Footage of two distinct but related scenes alternate for a few seconds each on a video monitor turned vertically and propped against the wall. The first is a closeup of a small, pretty-in-pink ballerina twirling inside a jewellery box to the tinkling of Tchaikovsky’s ‘Sugar Plum Fairy’. The other depicts a rotisserie kebab, the meat rotating slowly to the sound of a grating mechanical growl. Contrasting colour and sound in this way while using movement to align two entirely opposed images allows Buckley to probe stereotypical depictions of femininity, from a fantasy of socially acceptable girlhood to the commodification of women’s bodies under extractive capitalism. The work deepens in complexity over time and is a reminder that every generation of young women artists must navigate for themselves processes of socialisation as a girl and the no less uncertain terrain of young womanhood. Or, as Buckley puts it, ‘what it can mean to be “she”’.

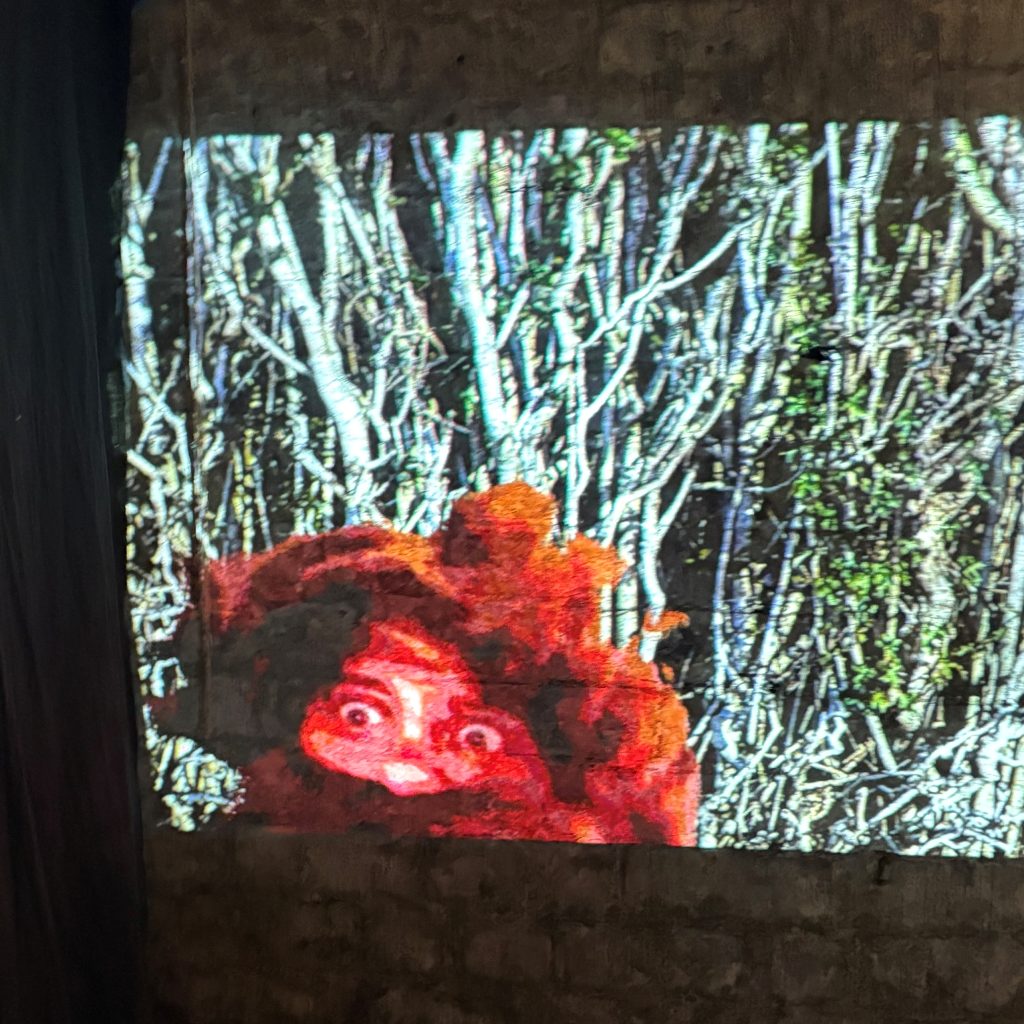

Sound connects Buckley’s video with other works in the exhibition. In the corner opposite is Rory Flynn’s projection and soundtrack ‘Sacred Toads and the Creation of Fire’ (2025). Apparently depicting a scene from the artist’s yet-to-be-published sci-fi novel, it overlays visuals of a waterway, a toad, a leopard, and woodland with flickering flames, totemic symbols and concentric circles of colour that expand outwards from the centre of the frame. The soundtrack accompanying this difficult-to-penetrate personal mythology is a low hum which is periodically in synch with that emanating from Ben Rowan’s untitled sculptural installation at the other end of the basement. This combines twigs, a Chladni plate – a square of thin metal covered with fine sand that vibrates at certain frequencies so that sound waves can be visualised as complex, geometric patterns – and audio equipment including a pair of speakers. The latter emit ‘naturally occurring frequencies from our planet’, albeit at a low level that requires the listener to lean in close.

Placed between the works by Flynn and Rowan, and occupying a space in and upon the dividing wall, are works by Liz Samways and Matteus Watson. Samways’ ‘Wild Hunt’ (2025) draws on the Norse myth of a procession of ghostly riders, who are said to sweep across the sky during Winter Solstice. Here the horses are rendered in outlines of bent wire suspended against a canvas that fills a rectangular void in the wall. Backlit, the effect of their shadows when seen from the other side takes on the appealingly delicate quality of traditional Japanese painting on silk or paper. Additional elements of the installation include a leporello-folded riso print that brings together Samways’ studies exploring the movement of horses with reproductions of Eadweard Muybridge’s late nineteenth-century photographic studies of the same. Watson’s subtle interventions include a pile of ash camouflaged against the basement’s stone flags, sheets of white A4 printer paper accumulating on the floor and covered in shoe prints, plus two freestanding timber structures, which, unadorned with colour or material, form apertures akin to doors or windows.

Two smaller sculptures are mounted on the walls. One, by Shannon Berry, is visually reminiscent of a spiderweb, but is larger, three-dimensionally complex and structurally more robust. Constructed from jet black cord, it hugs the upper corner of the room. It is a recreation of a ‘soot tag’, the strange phenomena of web-like strands of carbon and tar that form in the aftermath of a fire. Opposite is a mask sculpted in relief by the artist Idia. Constructed from yellow beads, it is lit from within to emit a golden glow. Beyond, in the basement’s second room, the chimney breast is rendered as another face by the artist Aparna’s installation of a torrent of autumn-hued leaves that spew from its open ‘mouth’, the empty space once occupied by a grate, thereby bringing the outside in. Three screenprints, also depicting leaves, are mounted unframed on the chimney breast above. Finally, Watson has installed a frosted acrylic cube, framed by black drapes and accompanied by the sound of quiet breathing, in that recess at the foot of the stairs.

What to make of these complex and sometimes large-scale works, installed as they are in such close proximity within a space filled with highly specific connotations? Far from the basement of populist American film and TV – alternating between wholesomeness and horror – this basement conjures unfortunate but inescapable associations with true crime of a specifically British kind, particularly for women and girls. It’s in the crumbling brick and plaster walls and in the flagstones that beg speculation on what lies beneath. It’s in the quality of the air, especially on a day like today when water seeps into clothing and earth.

This basement’s materiality is concrete and undeniable. Traces of former exhibitions linger in corners and cling to walls and ceiling, like ghosts reluctant to depart. Some of the works in Ethereal Matter, particularly those by Buckley, Watson, Berry and Aparna, to differing degrees, lean into this and make a virtue of the architecture and domestic context. As do Bruff’s cyanotypes upstairs in the kitchen, which also depict small domestic interiors – in this case the archetypal student bedroom. The installations by Flynn, Samways and Rowan, however, feel constrained by the scale of the space and unfortunately this also cramps engagement with them. This does not erode my appreciation that all are intriguing and show promise for the future when realised in a more expansive setting.

Regarding the works thematically brings them into more successful dialogue with each other. Ethereal Matter is billed as a collection of works about ‘the mutation of matter and ruptured roots’. On the publicity, the ‘E’ of ‘Ethereal’ is deliberately muted so that the title almost reads as ‘the real’, suggesting a back and forth between the tangible and the intangible. Several works are on surer ground here. Berry proposes her soot-tag sculpture as a ‘living entity’ that hovers between the real world and the next. Suspended in time, Aparna’s autumn leaves also oscillate between presence and absence. Idia’s golden mask seeks to explore Nigerian cosmology with contemporary materials by conjuring the Ogbanje, spirits of duality and transformations. Rowan retunes naturally occurring frequencies for the unsophisticated ears of humans, thereby rendering the inaudible audible. Through Buckley’s juxtaposition of images, promises made during girlhood evaporate into thin air when confronted by counterpoints in the real (adult) world. Bruff’s cyanotypes might also be susceptible to fading unless preserved with care, an apt metaphor perhaps for relationships nurtured during this phase of young adulthood.

Satisfying connections emerge throughout Ethereal Matter across notions of human and more-than-human relationships, the passage into adulthood, growth and decay, personal and cultural mythology, the worldly and the supernatural. The project successfully proposes a possible future for fine art pedagogy and practice in Leeds that affords students the opportunity to experiment in real-world art spaces and with the kind of encouraging and supportive framework that BasementArtsProject has created here. This is not a merely transactional relationship between artist and art space, but one which encourages early-career artists to think critically about context, community, the social value of art and encounters with publics. To focus overly on aspects of the works that are yet to find successful form or resolution would be to negate the real value of engaging phenomenologically with Basement, its ways of working and its specific context – although I’d certainly advocate for the importance of enhanced curatorial support as part of the mix too.

Dr Kerry Harker is a curator and researcher based in Leeds.

Ethereal Matter is at BasementArtsProject from 10 December 2025 to 23 February 2026.

This piece was supported by BasementArtsProjects and Leeds Beckett University.

Published 13.02.2026 by Benjamin Barra in Reviews

1,620 words