Belonging is rarely simple. It can feel like a warm tether or a boundary, a place of safety or a reminder of exclusion, making us question, ‘Where do we actually belong?’. Does a sense of belonging stem from a physical place, a community, or a prescribed social or geographical framework? The Inside and Outside of Belonging, the 2025 MA Fine Art Degree Show at the University of Leeds, brings together five artists whose work navigates all of the complexities of belonging with both intimacy and critique. Five artists – Annie Greenwood, Hsin Tien, Huayu Zhang, Kirstin Harvie and Isobel Richards – present distinct bodies of work, the culmination of their time on the MA Fine Art programme. Themes of memory, identity and power are brought to bear through this probing of belonging in an array of divergent visual languages and practices. Through installations, video works, painting and sculpture, there is an overarching questioning and dialogue about how belonging is felt, denied or constructed.

A group hang on the first floor welcomes visitors with a rich mix of work from video to delicate paper works and large portraits on board and canvas. Each artist’s voice and style comes across with a clarity that makes me eager to venture upstairs and learn more about their distinctive practices.

I begin with Hsin Tien’s paintings, which range from large colourful canvases that bend under their own weight to smaller jewel-like panels dense with detail. Trees, shrubs, and familiar street scenes recur in their work. Colour is a careful language in these fragments of memory; some are pulled into focus, others seem to be dissolving into loose washes of coral and green. A red lamp post becomes monumental, a castle recedes quietly and the artist’s own sense of home becomes familiar as I walk amongst their work, spotting recurring motifs. In one small room, a continuous painted canvas wraps the walls, its start and end dates inscribed directly onto the gallery wall, turning the space into a visual diary. This gesture is evocative but feels transitional — like a sketchbook page scaled up. Beyond the dates, the idea seems unfinished, as though this work could mark the beginning of a new approach, expanding their work beyond standard format canvases and experimenting with an installation of sorts. Tien’s painterly language, however, is evocative: the use of colour and approach to small everyday objects as well as landscapes from memory, shows confidence and a dedication to creating their own visual language of home.

If Tien’s work maps memory through colour and motif, Isobel Richards’ ‘Right to Roam’ (2025), takes a more archival approach. Her installation leads visitors along a simple route, marked by ramps, a curtain and scattered text fragments, prompting pauses and participation — we are asked to act, to look, to pace the space. Rectangular sections cut in the fabric dividing the space act as peep holes, reminiscent of viewing holes in hoardings, or letterboxes, a porthole through which other worlds can be seen.

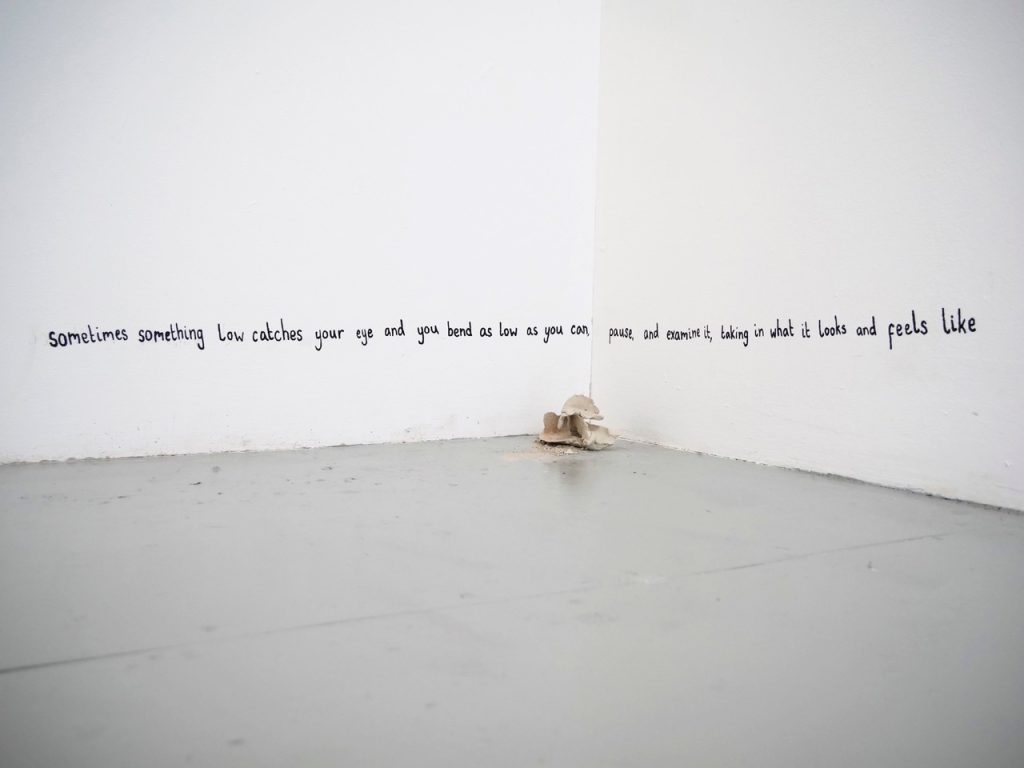

Text is scattered throughout the installation and the items on display, including in the form of small handmade books. The language and its placement are playful yet considered. Written down in corners that make me squat to inspect a broken shard of pottery on the ground or welcoming me at intervals as I traverse the space, it pulls in wider social politics. It reminds me of ‘dividing lines, fences, barriers, blockades and checkpoints’, and their existence everywhere, from the Lake District’s rolling hills to contested country borders.

Richards’ accompanying video in the group show gallery, ‘Looking’ (2025), takes a different tack. Zooming into the micro-dramas of insects and seeds, the film has an attentiveness that feels meditative. Richards’ sensitivity is striking, but the stripped back nature of the installation risks fading into the white cube environment compared to the dense, rich colours and worlds on the screen. ‘Right to Roam’ seems to yearn for a wilder, more tactile setting that would bring me up close and personal with the worlds she depicts brilliantly in the opening text that greets visitors: ‘…people cannot be contained, and like nature, reality always finds a way through the cracks; like weeds through concrete, fungi through stone walls, spiders up drainpipes…’. We’re invited to think about power, access and land, but the access here is all relatively smooth and easy to navigate. I’m aching for a really awkward stile to navigate or squeeze through, a close encounter with a stinging nettle perhaps. The curation of fragments of thought, whether sketched in watercolour or written in notebooks, is both a strength and a limitation here. The work reflects a quiet politics of observation and leaves space to drift. I move onto the next space with a head full of questions, as I discover more text, like way-finding arrows on a walking route, dotted down the corridor as I leave:

here in this place

that feels like ours

but at the same time

it’s not our place

and not our rules

Kirstin Harvie’s work provides a stark counterpoint, commanding attention with its psychologically intense and considered series of portraits. Her portraits focus on the 107 individuals who are serving or have served whole-life orders in England and Wales. Harvie explores the visual politics of crime and justice, taking on this heavy and complex subject with admirable neutrality and ethical awareness. The only artist of the MA cohort to stray from the autobiographical interpretation of belonging. Her work is both visually arresting and conceptually layered, raising questions about justice, empathy, representation and the impact their crimes, their imprisonment, and their portrayal in the media have had on each individual, disrupting the visual information through fragmenting and layering. ‘Everyone’ (2025), a grid of printed acrylic portraits, layers four individuals together, with twenty-seven prints stacked and mounted on a wooden divider. No individual can be clearly identified, referencing both the ‘atavistic form’, the pseudo-scientific attempt to identify criminal types, and prison architecture. The studies confront viewers with the uneasy tension between visibility and erasure, as well as individual humanity and systemic control.

In ‘Alan Maidment’ (2025), Harvie paints over vertically printed newspaper articles, allowing their language — sensationalist, accusatory — to bleed through. The technique implicates media narratives in framing these lives, while Harvie’s working into the image insists on complexities and points to missing information regarding each individual. The portraits are stark but somehow never veer into the voyeuristic, balancing moral complexity with technical skill. Harvie neither absolves nor sensationalises; instead, she holds us in an uncomfortable space of looking, where empathy and repulsion coexist.

Harvie’s ability to weave formal precision and conceptual inquiry is striking and memorable. Her use of fragmented panels and layered text as base materials resonates with belonging and exclusion on a systemic level, interrogating how incarceration and public perception define who is remembered and who is discarded or forgotten. Yet Harvie’s sincerity and attention to detail prevents the work from falling into cliché, demonstrating a level of maturity that feels like a foundation for a formidable practice.

Where Harvie’s portraits grapple with institutional belonging, Huayu Zhang’s work oscillates between external landscapes and intimate internal worlds and seasons. ‘Wintertime’ captures the University of Leeds campus and the famous Roger Stevens Building in icy blues. In ‘Cold Breath – a Four Panel Polyptych’ (2025), threads of yarn connect canvases like waypoints on a map. It is Zhang’s ‘Soul Bark’ (2025) ceramics that stand apart and ask something else of this subject, in a way that is both visceral and captivating. Hollowed tree trunks cradle foetal forms and heart-like organs, glazed in vivid blue that drips like veins. These sculptures feel alive, with organic roots gripping the plinths and an outer layer protecting forms, possibly representing other lived experiences, beneath their surface.

Zhang’s practice unfolds like a rich narrative, shifting between paintings, ceramics and polyptychs, each chapter feeling like a part of an epic story. At times, this ambition diffuses impact; a few paintings feel like studies rather than resolved works. But the strongest pieces — particularly ‘Soul Bark’ — are unforgettable, demonstrating Zhang’s ability to use materiality to evoke both vulnerability and power.

Annie Greenwood’s ‘Just Five More Minutes’ (2025) closes the loop with an installation that feels at once domestic and theatrical. Visitors step into a lavender-scented space, filled with vintage furniture, frames, kitsch ornaments, slippers and lamps. There is a hallway space that serves as a welcome pause, helping me to transition from the white gallery space to a more familial and soft environment. Homely. Beyond a dividing curtain, mismatched chairs face two screens and play two ‘acts’ – short films with overlapping text. The elements that fill the space are placed with care, and I spot a familiar Frank Sinatra CD that I recognise from my own parents’ house. Predominantly working with moving image, Greenwood’s work deals with family and memory with tenderness, with notes of loss and grief. It also carries a slightly cloying sweetness, its nostalgic sentimentality teetering on the edge of overdetermination and directiveness.

The careful staging invites complete immersion into a built world, evoking a collective sense of familial intimacy and a tension of wanting to both hold tight and let go of memories. Greenwood’s work feels both deeply personal and universally familiar. The installation is tethered firmly in style and direction to the video work ‘The Further I Go’ (2025) presented in the group show, which immerses us deeper into a mysterious derelict building. Both pieces raise questions of time –its slippage and passing, and of what is left behind by loved ones in physical spaces, or of the time shared in their company.

The work inhabits the uncomfortable spaces of loss, memory, and the desire to forget.

The Inside and Outside of Belonging brings together five very different practices, each circling the question of how and where we find connection. Tien’s tender cartographies of home, Richards’ fragmentary field notes, Harvie’s institutional critiques, Zhang’s shifting landscapes, and Greenwood’s domestic scenes all speak in distinct registers, yet sit together as a conversation. Belonging emerges here not as something fixed, but as something provisional – a state made and unmade by stories, systems and spaces.

The exhibition also carries the unmistakable rhythm of a degree show: moments of confidence alongside works that feel like steps in progress. Tien’s canvas-lined room or Zhang’s sprawling polyptychs hint at directions not yet fully realised, while Harvie’s portraits have a sharpness of intent that could hold the weight of a solo presentation. Rather than smoothing over these differences, the show lets them stand – reminding us that experimentation is as central to learning as resolution.

What lingers is less a definitive statement than a series of prompts: fragments that stick, images that unsettle, moments of recognition and estrangement. Vulnerability and ambition have equally been embraced by this cohort, giving the exhibition a sense of openness – alive to the possibility that belonging, as posed in the opening of this show, will always be slightly elusive, shifting, and up for negotiation.

Joanna Jowett is a writer, artist and producer based in Leeds and is also co-director of Copypages.org, an artist’s publishing platform.

The Inside and Outside of Belonging ran from the 2-6th of September in the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies at the University of Leeds. https://ahc.leeds.ac.uk/fine-art

This review is supported by the University of Leeds.

Published 29.09.2025 by Lesley Guy in Reviews

1,972 words